Beauty e-commerce startup and new JCPenney partner Thirteen Lune has been promoted on the Instagrams of celebrities such as actress Constance Zimmer, model Larsen Thompson and influencer Stephanie Shepard, but not as paid influencer promos.

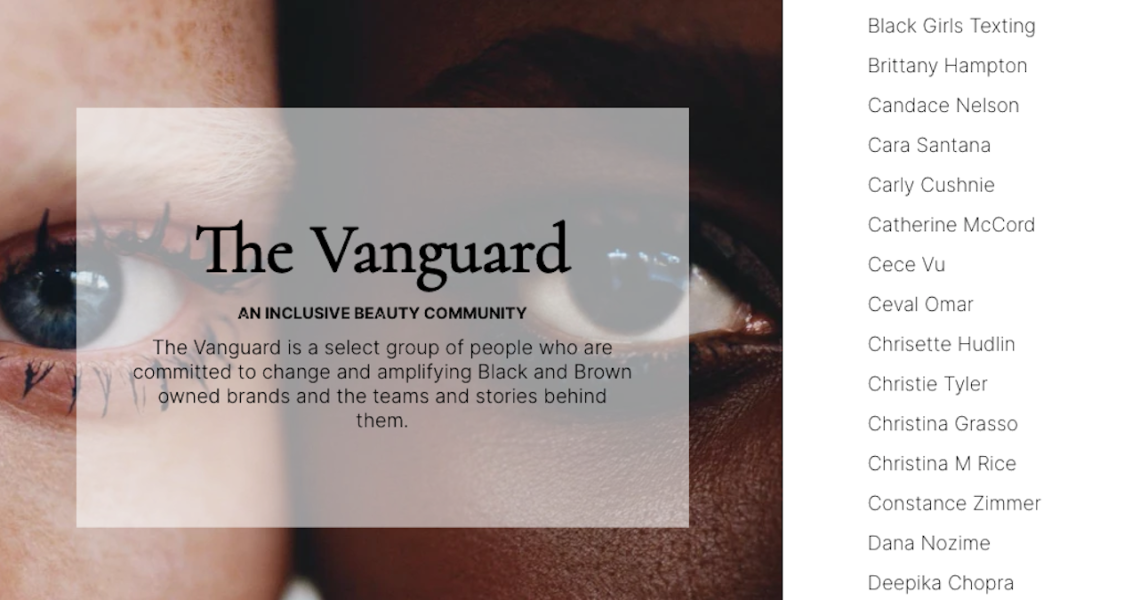

These are a few of the members of the e-tailer’s “Vanguard” group, a mix of celebrities, influencers and other public figures that advocate for the e-tailer online free of charge. In the beauty world, this group is not the only one of its kind, as a growing number of new brands including Humanrace, Keys Soulcare and Ceylon Skincare have created public-facing communities that advocate for them online without compensation. For brands, this organic route to brand awareness offers content that feels less like sponcon than that of a traditional pay-for-play influencer deal.

“Thirteen Lune is all about authenticity and telling an authentic story, and so we wanted to tap into that part of our ethos and our business from day one, which is support for a mission-driven business and a first-of-its-kind, truly inclusive retail platform. That didn’t feel like something we should have to pay for,” said Thirteen Lune founder and CEO Nyakio Greco.

Thirteen Lune’s Vanguard includes Selma Blair, Naomi Watts, makeup artists like Katie Jane Hughes and Monika Blunder, as well as models, tech execs and brand founders. The company has done no paid influencer or celebrity marketing since launching in December 2020. While some of Thirteen Lune’s Vanguard members such as Watts are investors, the majority are not.

“They were all asked to be part of the Vanguard because they were people that were, from day one — long before the summer of 2020 — really passionate about moving the needle for change,” said Greco.

Other brands with similar groups include Pharrell’s skin-care brand Humanrace with its “Well Beings” featuring members such as Tyler, the Creator, and Alicia Keys’ new brand Keys Soulcare with its brand community that it calls “Lightworkers.” And although major celebrities can afford to promote brands they like sans fee, the model is also being used with micro influencers: startup Ceylon Skincare created its “City Boys Council” featuring fellow startup founders and creatives.

These groups are being formed at a time when consumers are experiencing “influencer fatigue,” or feelings that influencer content is inauthentic.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

“Influencer fatigue is a thing because, ultimately, sometimes it doesn’t feel authentic. It just feels like they’re doing this because they’re being paid to do something. And to that extent, our Lightworker community is 100% different than that, because it’s there to help foster connections to each other, as well as for brand,” said Nichole Kirtley, the senior director of brand extensions at Keys Soulcare parent company E.l.f. Beauty.

The Lightworkers include anyone that is a fan of the brand, including any celebrities that have participated in brand events or content such as Deepak Chopra, Misty Copeland and Rickey Thompson.

Members of these groups are involved in creating a range of content for the brands. They’re often featured on the brands’ site and social content such as articles and podcasts, and in some cases write their own articles. They also participate in brand events and post content in support of the brand, as well as test products.

Like Thirteen Lune, Ceylon Skincare (which is sold through Thirteen Lune) also does not spend anything on traditional influencer marketing. Its City Boy Council members are seen in social media content, write for its brand publication, participate in monthly Clubhouse talks and create Spotify playlists for the brand. In the fourth quarter of this year, the brand plans to launch a media arm with a digital TV series featuring the members.

“We just like each other. That’s how real the love is,” said Ceylon founder and CEO Patrick Boateng. “We don’t look at them and say ‘Hey man, go post this thing; you have this conversion rate, here’s this metric.'” The model rejects traditional ideas of transactions associated with influencer marketing.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

“I love the word ‘community.’ It’s often been overused and abused over the years,” said Kwame Garrett-Price, the founder of leather goods brand Cal & Kay and a member of Ceylon’s council. He is featured in Ceylon social content and has written articles about topics such as love for the brand’s publication. “If they tried to pay me, I don’t know if I would even do it. I don’t care. It’s all love; it’s all good.”

While brands have long been concerned about how to make influencer content authentic in the era of #sponcon, consumers became especially frustrated with aspirational influencer content during the pandemic.

“The pandemic has heightened and accelerated the perceptions around the idea of seeming out of touch,” said Saisangeeth Daswani, the head of advisory for beauty, fashion and APAC at trends forecasting firm Stylus. “A lot of day-to-day consumers have felt that some of these influencers have lived in their bubble of privilege.”

Members that participate in the brand groups are able to achieve publicity, either through participating in high-profile events with celebrity founders such as Pharrell or Alicia Keys or through mutual promotions of startups for smaller brands. But all insist that the relationship is not transactional.

“With friends who ask me to do things, I never say, ‘Yeah man, here. Let me get these with you.’ We just don’t operate on that level. That’s not the frequency we work with,” said Boateng.