If you’ve spent any amount of time on beauty TikTok, you’re likely aware of the “glow up” trend. Set to different sounds over the years, included videos feature an influencer transitioning from a bare face to a full-glam look. Recently, however, that style has been turned on its head to bring scrutiny to the face-altering effects of beauty filters.

Clearing blemishes, softening skin and reshaping jawlines, beauty filters are widely used among social media users across age groups. But with concerns about unrealistic beauty standards and their effects on mental health, Gen Z is starting to say it’s had enough. The rise of “filter versus reality” posts on TikTok and Instagram Reels shows influencers’ and regular users’ growing backlash against filters, with the hashtag #filtervsreality currently up to 114.5 million views on TikTok. Meanwhile, advertising regulators, agencies, brands and retailers are beginning to eschew the practice in promotional content.

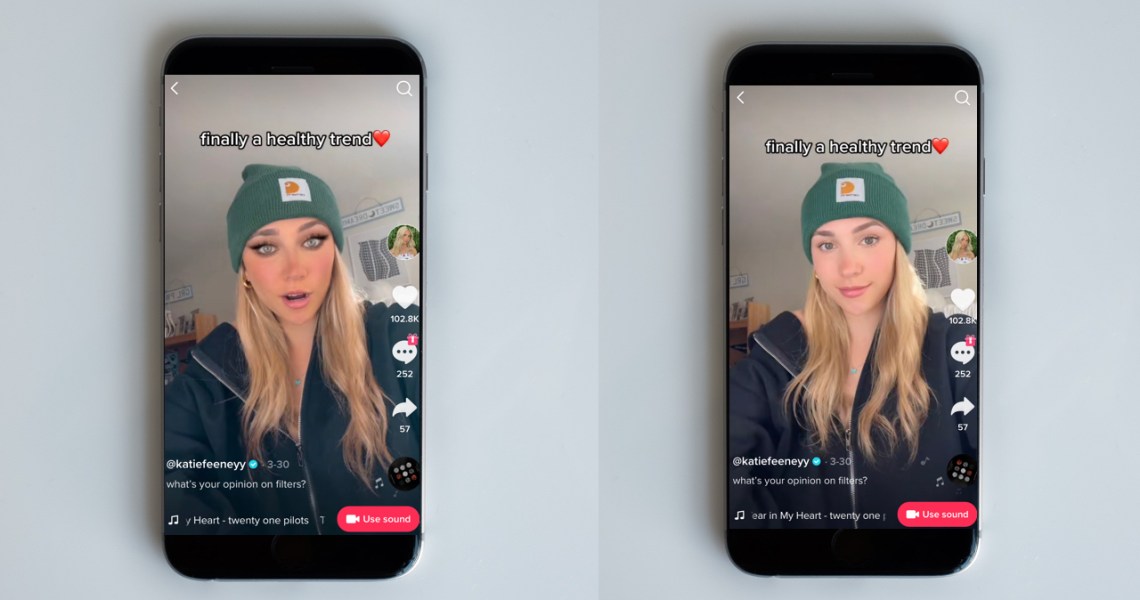

In late March and early April, major influencers including Charli D’Amelio (141.8 million followers), Brooke Monke (20.3 million) and Katie Feeney (6.9 million), as well as actress Ashley Tisdale, drove a viral trend to the sound of a Twenty One Pilots’ song that poked fun at the concept of filters. Influencers taking part in the trend appeared in an over-the-top AI beauty filter before turning it off to show their natural face. Like the “glow up” format, these anti-filter videos have been trending across a range of different viral audio tracks on both TikTok and Reels, such as the “This is not my face” audio that recently went viral.

These videos are in reaction to widespread filter use among Gen Z. According to survey data from student loyalty network Student Beans, 57% of U.K. and 62% of U.S. Gen-Z respondents use filters on their social media posts. For 43% in the U.K. and 23% in the U.S., the purpose of doing so is to “significantly” alter how they look. A City University of London study found even more extreme numbers, citing that 90% of young women use social media filters. However, the stat reflected the use of all filters, including those adding dog ears or changing images to black-and-white.

“With these filters,, [you] have symmetrical features, you have cat eyes, you have big lips, you have a slim nose, a contoured face — that is truly what society wants every woman to look like. For every single person with a phone to have access to that within a split second is beyond worrying,” said Sasha Pallari, a model, makeup artist and influencer who started the anti-filter #FilterDrop campaign on Instagram in July 2020. As part of her campaign, she showed a video of her face with and without a filter, and noticed an immediate response from people who joined in by posting their own videos and side-by-side photos. She hosts a video series of interviews as part of her #FilterDrop campaign that sponsored by beauty companies including Clarins, E.l.f. Beauty, Urban Decay, Cult Beauty and Beauty Pie, among others.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

Another thing she noticed: Influencers were frequently using filters in sponsored content, making claims about the effects of beauty products based on altered images and videos. Based in the U.K., Pallari decided to report this to the U.K.’s Advertising Standards Authority. By February 2021, the government regulator had made a decision to ban influencers from using “misleading” filters that “exaggerate the effect of a cosmetic or skincare” on social media. In the same month, the authority handed down rulings against two influencers that had used filters to make claims about the effectiveness of tanning products.

Following the ASA’s announcement, brands and companies have started to get on board with the trend. Huda Kattan pledged to not use filters in March 2021. In April this year, Ogilvy U.K. announced that it will stop working with influencers using filters.

While the U.S. FTC has not enacted a similar policy, CVS has taken a stand against filters in the U.S. As part of its Beauty Mark policy of transparency on image alterations launched in 2018, the retailer forbids influencers from using filters in its sponsored content on social media.

“Our role as a retailer has really been to bring the conversation to the forefront for brands and to influence,” said Andrea Harrison, vp of merchandising for beauty and personal care at CVS. The retailer has been upping its influencer marketing, she said, as “social media is the way so many customers find their beauty products first, and it’s the first place they see how well they work.” Since implementing the ban, CVS has worked with over 1,000 influencers who have earned over 90 million impressions on sponsored content without filters.

To highlight its ban on filters, CVS launched the 10-day #CVSFilterDetox challenge across social platforms in October 2021. For the campaign, CVS created a branded filter on TikTok and Snapchat featuring users in a heavily altered AI makeup look that would disappear to reveal their face. It also called on participants to refrain from using any filters on their social content for the 10-day period. Influencers and social media personalities including Peleton star and makeup artist Tunde Oyeneyin, mental health-focused influencer Victoria Garrick and psychologist Dr. Mariel Buque participated. The branded filters were used and saved close to 400,000 times on Snapchat, and the campaign received over 49 million views on Snapchat, TikTok and Instagram, according to CVS.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

The main message of CVS’s efforts has been the mental health effects of altered images. As part of its digital initiatives, it teamed with media psychologist Dr. Pamela Rutledge and consulting and research firm The Harris Poll to conduct a study on women ages 18-35, finding that 45% of those who spend time on video calls weekly use filters to alter their appearance.

“Developmentally, the whole task of preteens, teens to young adults is figuring out who you are and how to make your place in the world,” said Rutledge. “People in those ages are going to be much more vulnerable to social validation and social feedback.”

According to Rutledge, using filters once in a while is not necessarily a problem, but “the danger there is when people start changing their image so that they no longer feel confident putting a picture up that isn’t altered,” she said. This creates an image of an “ideal self that we can never meet.”

“It’s not like, ‘Do I look like that influencer or this model?’ It’s ‘I don’t look like myself to me,’” she said.

But amid excessive filter use, signs are pointing to the fact that Gen Z is getting more savvy. According to Student Beans, 88% of survey respondents said they can tell the difference between a post that features a filter and one that doesn’t. Among U.S. responents, 52% believe public figures should have to disclose when they’re using a filter.

“The Gen-Z generation needs more credit for how switched-on they are to stuff like this,” said Pallari, of filters.

“The more they become familiar with the technology, the more they’re able to exercise critical thinking,” said Rutledge. “It’s that visual literacy that comes with understanding the technology.” But even with more awareness, it’s culture driving demand for these technologies in the first place.

“There are an awful lot of young people still feeling the pressure to look perfect,” she said. “We still see people being rewarded for being beautiful, rather than for what they do.”