Kerry Docherty, chief impact officer at fashion brand Faherty, said that several years ago, she began to feel uncomfortable with some of the prints in the brand’s collections that were clearly inspired by indigenous Native American patterns, yet had no connection to any actual Native designers or people.

At the time, she led the brand to mark the pieces as “indigenous-inspired.” But the longer she sat with it, the more felt the response was insufficient; she wanted to address the issue of cultural appropriation in a more direct way. So in 2016 she began working with indigenous designers to phase out the existing prints, which were not designed by indigenous people, and replace them with patterns and prints created in collaboration with Native American designers. Docherty said the brand hadn’t been called out or received any notable criticism prior.

The Black Lives Matter protests have forced many brands to do some soul searching in the last few months, with many reckoning with an ongoing lack of diversity and visibility for people of color. While Faherty’s efforts to improve its own product catalog predate the protests, they represent a model for how brands can identify, eliminate and replace problematic design choices as they seek to create a more equal fashion industry.

The key, Docherty said, is making an actual positive impact on people’s lives beyond the superficial. The “indigenous-inspired” tag her clothes had didn’t actually help any indigenous people.

“I started talking to a lot of indigenous people and I struck up a relationship with Doug Good Feather, who is a Native American musician, designer and activist,” Docherty said. “It took maybe a year of just talking to him and others before we started to put things into motion. I didn’t want it to be just a one-off transaction; we spent a lot of time building up a relationship.”

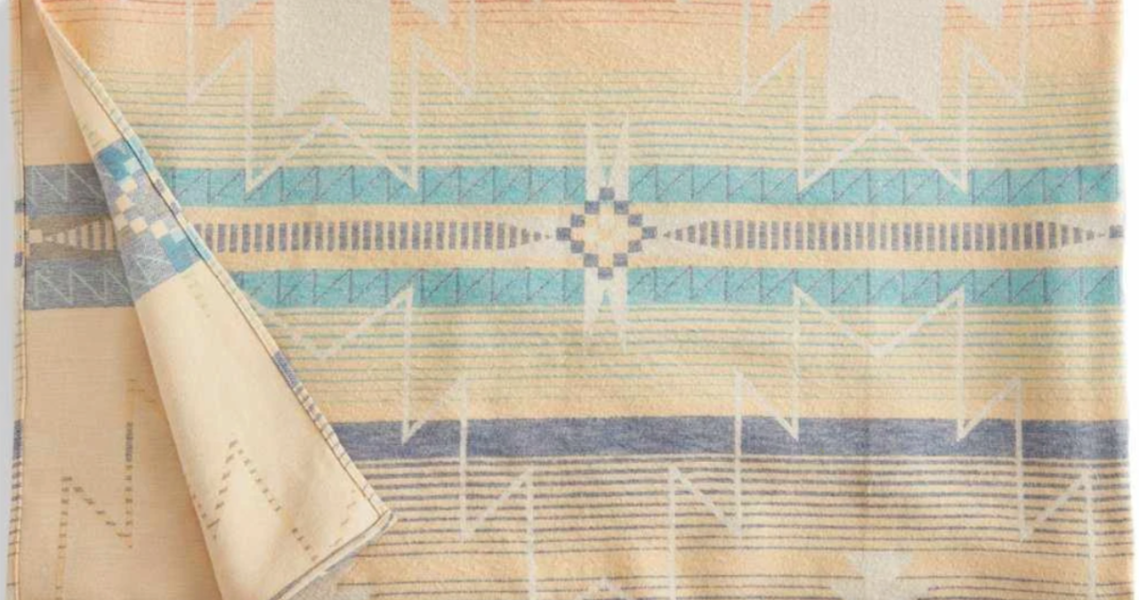

Faherty, which was bringing in $25 million per year in revenue as of 2018, began donating 100% of proceeds from its indigenous-inspired prints to Good Feather’s organization, the Lakota Way Healing Center. Good Feather has designed prints for the brand, and their proceeds will also go to his organization. Docherty said that, in April, Faherty donated an additional $10,000 to the IllumiNatives organization to help Navajo people who have been impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Faherty’s next step is launching a collection with indigenous designer Bethany Yellowtail around the holidays. Yellowtail has been an advisor and consultant to the brand for the last year, and the collection is the first of several planned collaborations between her and Faherty. Docherty also said the company has just confirmed that Crystal Echo Hawk, the CEO of IllumiNative and a member of the Pawnee tribe, will join the company’s board as its first indigenous member. The company declined to share the diversity breakdowns of its staff and board.

Ad position: web_incontent_pos1

“We still have some designs that are indigenous-inspired that were not created by indigenous people that we are phasing out, but as long as we have them, every sale will go to Doug’s organization,” said Docherty.

The idea that brands have a duty to marginalized people whose culture inspired their designs is one echoed by founders of color. Amber Tolliver, founder of lingerie brand Liberté, said it’s not enough just to acknowledge that debt with words.

“This moment is not just about appropriation of black culture, but it’s also about indigenous cultures,” Tolliver said. “The industry has appropriated a lot from people and it has a responsibility to give credit where credit is due. But it’s about more than just citing your sources. You have to uplift and amplify those people, as well. If fashion had as much respect for people as it does for the culture that inspires their clothes, we’d be a lot better off.”

Docherty said fashion has a blindspot when it comes to indigenous cultures in America. Brands like Urban Outfitters have long been criticized selling styles like feather headdresses, but more subtle details like prints, patterns and fringes that are inspired by Native Americans are not as obvious to the average non-Native consumer.

Ralph Lauren, for example, has come under fire over the years for using Native American prints and imagery (as in this catalog that featured images of Native Americans in a faux Old West setting) without acknowledgement or input from indigenous designers. (Coincidentally, Faherty creative director Mike Faherty got his start in fashion working at Ralph Lauren.) In 2016, Rebecca Taylor launched a collection called “Navajo,” but its name was swiftly changed after a negative reaction. Last year, Dior erred significantly when it debuted a Native-American-themed campaign for a fragrance named “Sauvage” (and featuring Johnny Depp, himself criticized for his portrayal of an indigenous character in the film “The Lone Ranger”).

Ad position: web_incontent_pos2

Docherty said Faherty has introduced several layers of approval — with consultants including Good Feather and Yellowtail — to all designs, whereas previously there was less of a strict system.

“There’s absolutely a blind spot around indigenous issues in fashion,” Docherty said. “There’s a $4 billion industry around indigenous-inspired jewelry dominated by non-indigenous designers. I don’t think people realize just how terribly Native Americans have been treated over the years, including today.”